Content

Given all the different formats I'm serving this content in, it was important from the beginning to have some sort of greatest-common-denominator structure containing not just the all content, but also some semantic information for presenting it well. Defining this structure allows me to know exactly what can be represented when writing content, as well as what a new presentation format must be able to represent.

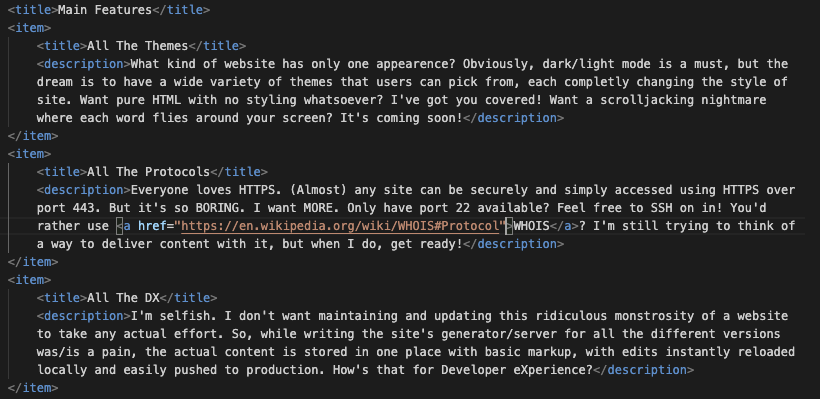

Take, for instance, this page. So far, you've encountered three sections: the Overview, Main Features, and now the Content. While all three are sections containing mostly text, the "Main Features" section serves a completly different purpose, being a list of broad goals with short descriptions rather than some general content with a header. Creating a new type of section for this in the content structure allows all formats to present such lists effectively, without having to customize each page for each presentation format. Not only that, but elements like the title and subtitle also need to go somewhere, and defining a content structure upfront forces me to clearly define what's allowed and not (for example, a subtitle contains hypertext, including links, while titles are plain text).

While something like Markdown is the typical choice for static-site generators, making writing typical posts a breeze, it just wouldn't do for this use case. I needed room for encoding custom structure along with my content. So I next turned to YAML, a "human-friendly data serialization language" that could surely encode the structure I wanted. However, trying to write content in YAML just didn't feel right (despite their website's success in doing so). So, I finally settled on everyone's favorite data format...

XML. I don't think I've met anyone who claims to like or promote XML's usage, and I don't know of any modern project that's chosen to use it with no external pressure, but I really like it for this use case. Its separate tag names, attributes, and tag contents map nicely to types of content, extra non-displayed information, and actual on-screen content. Take the humble link; XML can represent it with a simple <a> tag, with href attribute for the destination and (in theory) any textual content you want between the tags. Sure, you can do the same in JSON, but you don't get that clear delineation between the destination and the visual content, it's all just attributes.

The XML describing the Main Features section above. Beautiful, isn't it? (At this time, I have yet to add code blocks, so we'll all have to make do with screenshots.)

So, with all my XML files for projects, posts, and other pages stored in a content directory, I serialize it into one big content struct with using serde and quick_xml (along with some basic directory walking, I'm not (yet) crazy enough to put everyone in one XML file). Then, each format implementation (aka presenter) gets a reference to the content struct on rebuild, from which it creates and serves its presentation.