Datapath Overview

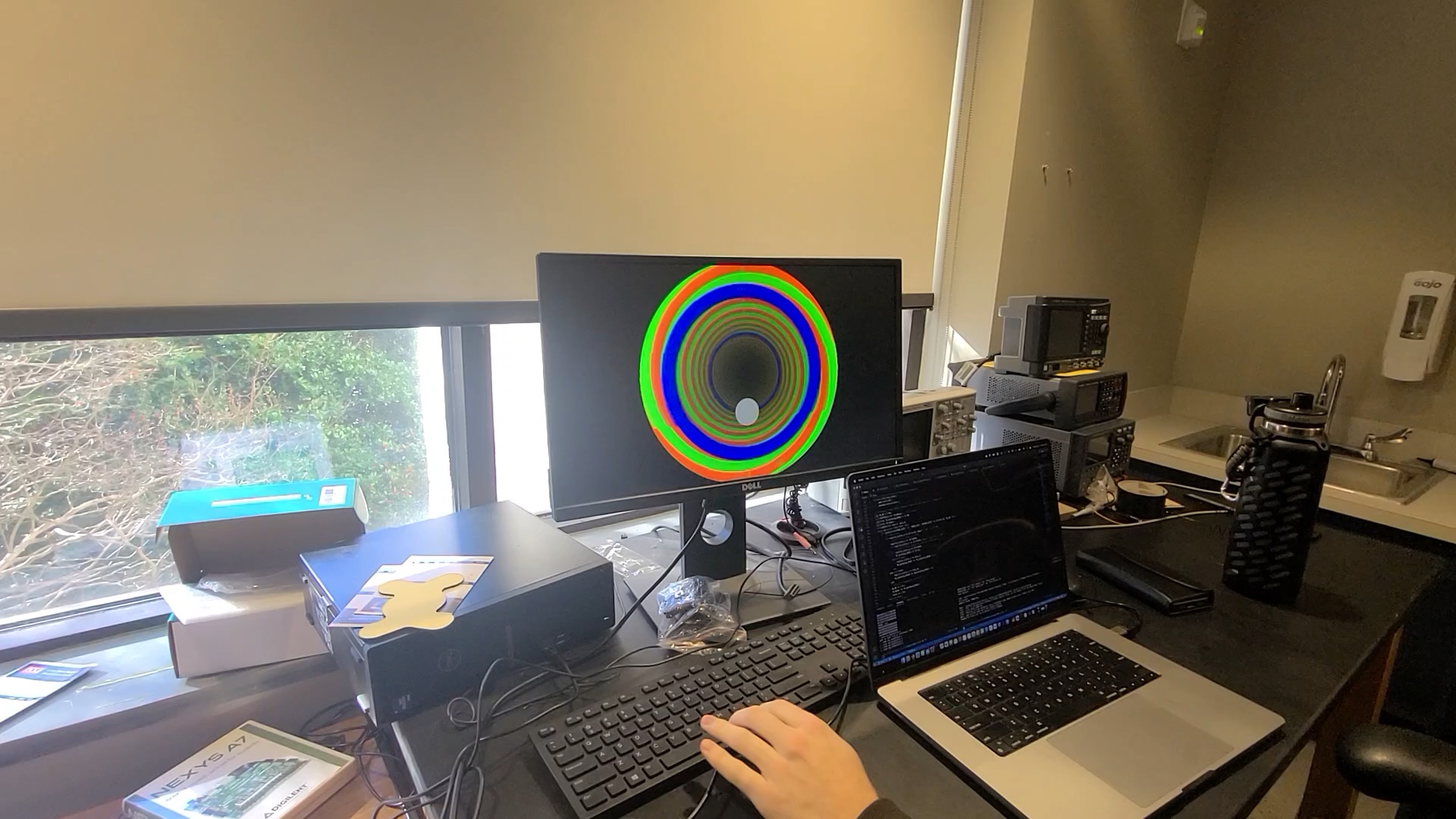

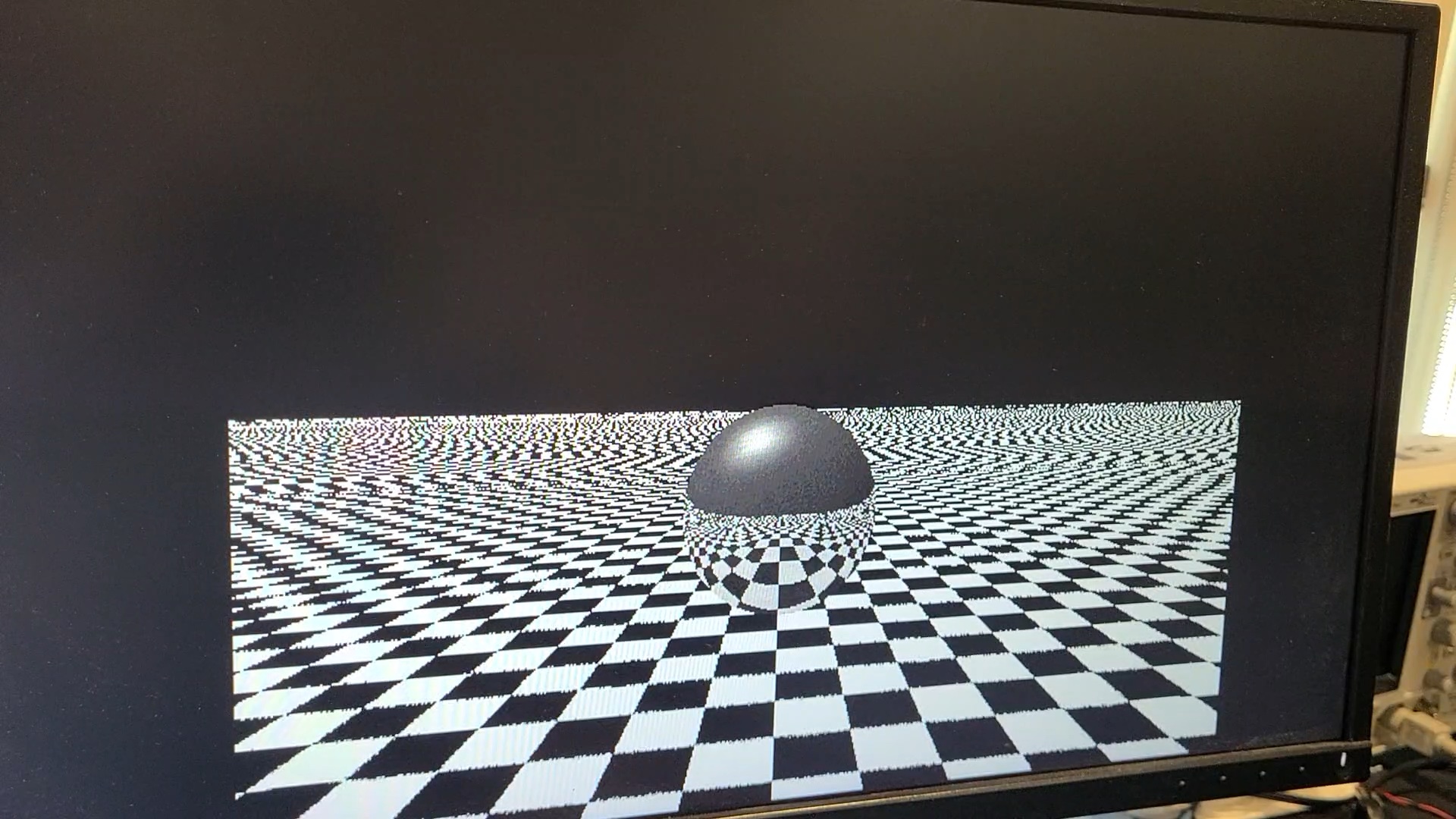

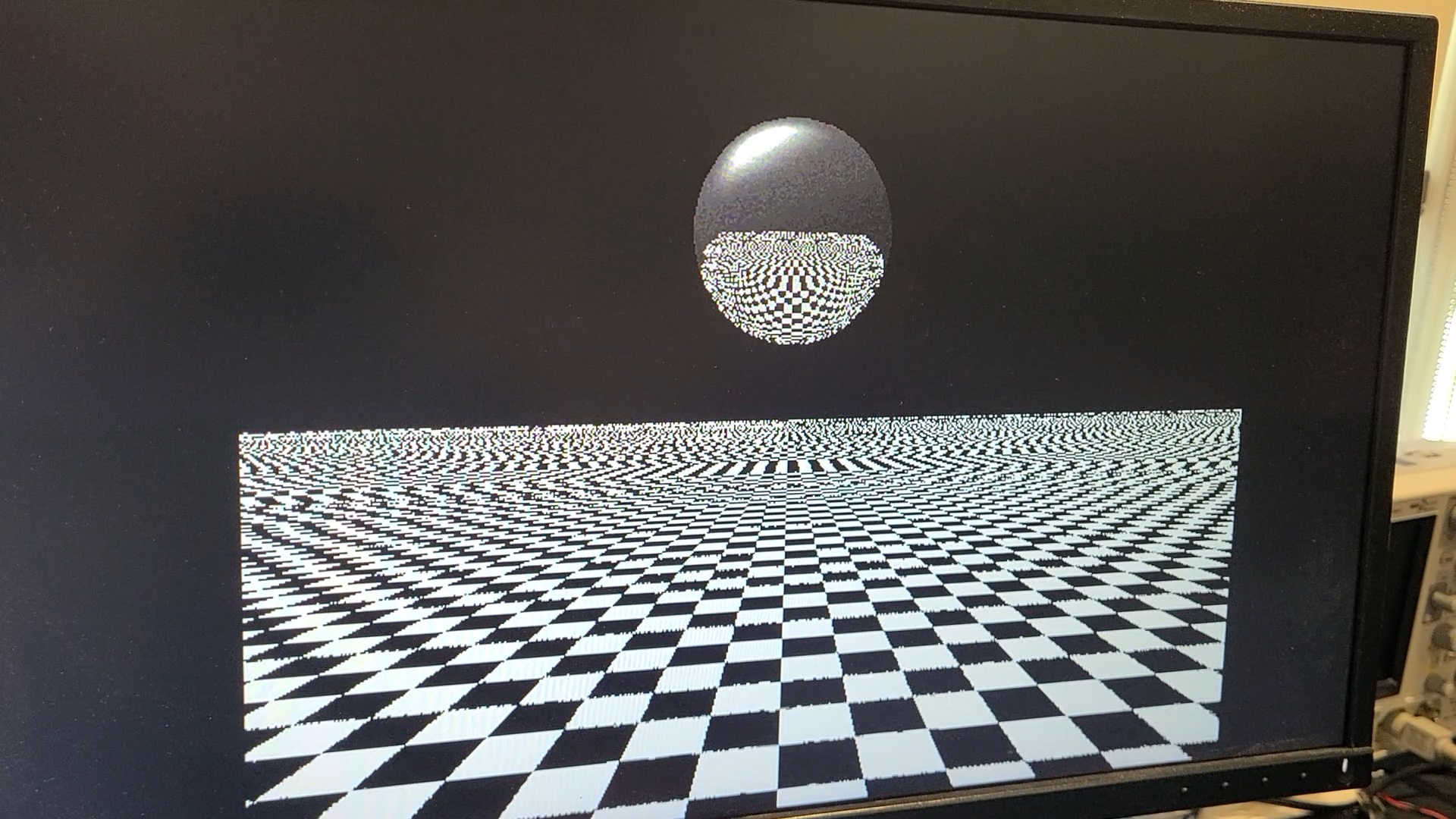

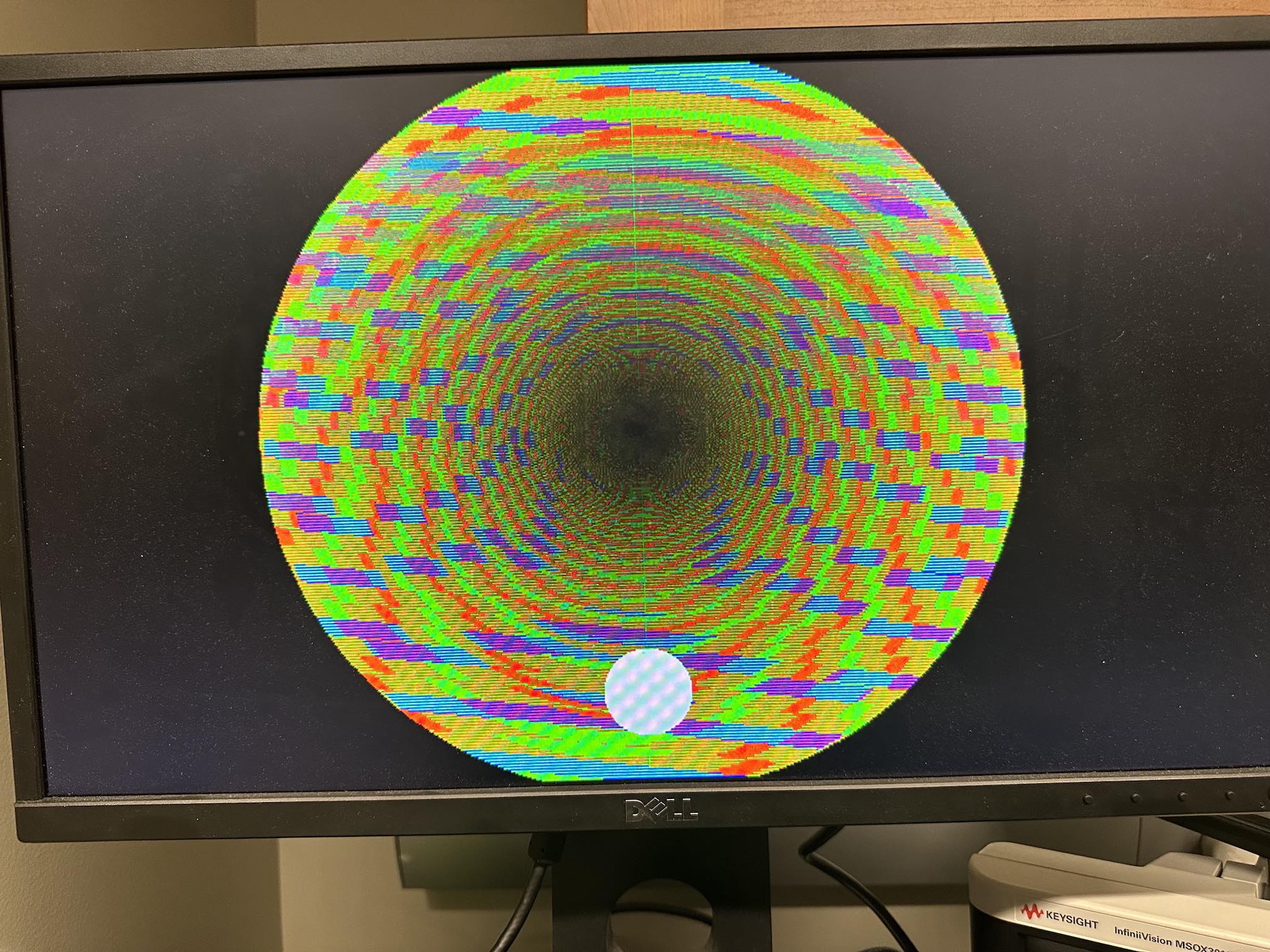

The GPU core has a 4 stage (Fetch, Decode, Execute, Writeback) vector pipeline, with 16 lanes. Of the 8 arithmetic operations supported, 5 are implemented with Vivado's Floating Point IP blocks, the 2 simplest (floor and abs) are implemented manually, and 1 (arctan divided by pi) uses a 2048-entry lookup table.

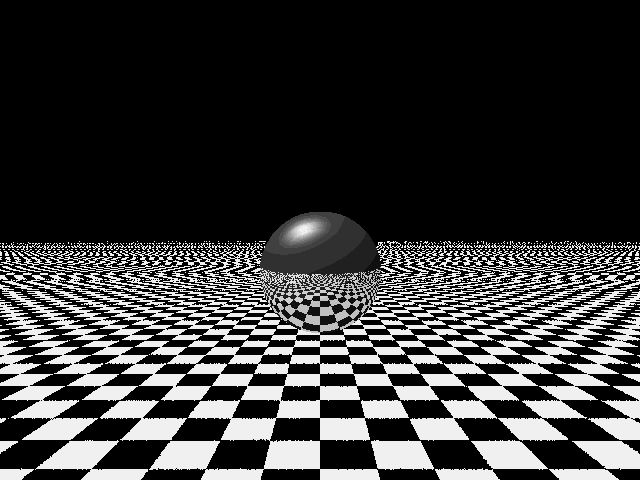

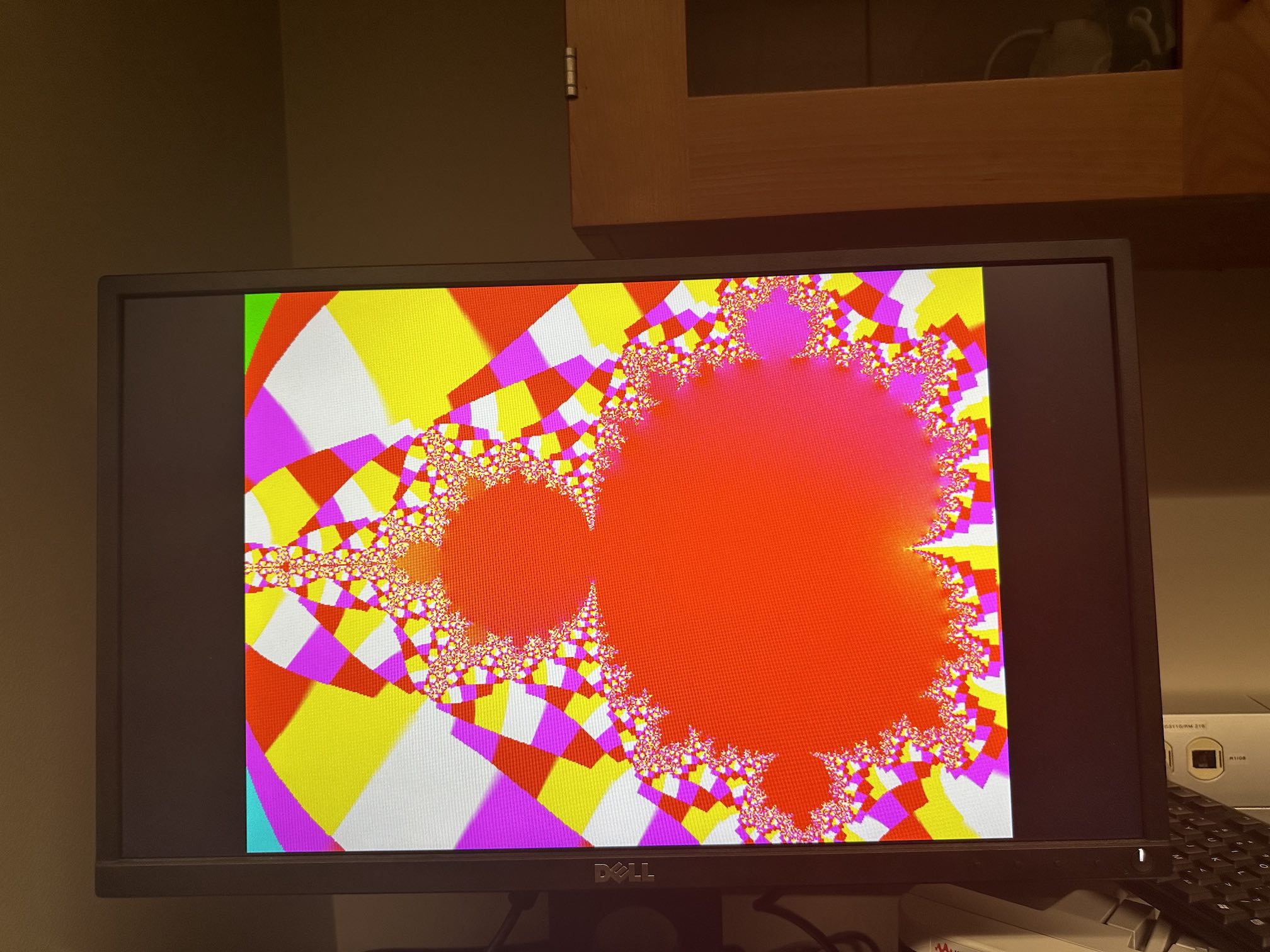

A simple wrapper/scheduler module runs the program once for each block of 16 pixels (left-to-right), setting registers for the x and y coordinates for use in the program. Once the program reaches a special "done" instruction, the resulting color (placed in 3 specail registers) is written to the framebuffer. A separate VGA output module scans through this framebuffer and outputs at 60fps, with no VSync or tearing mitigation to speak of.

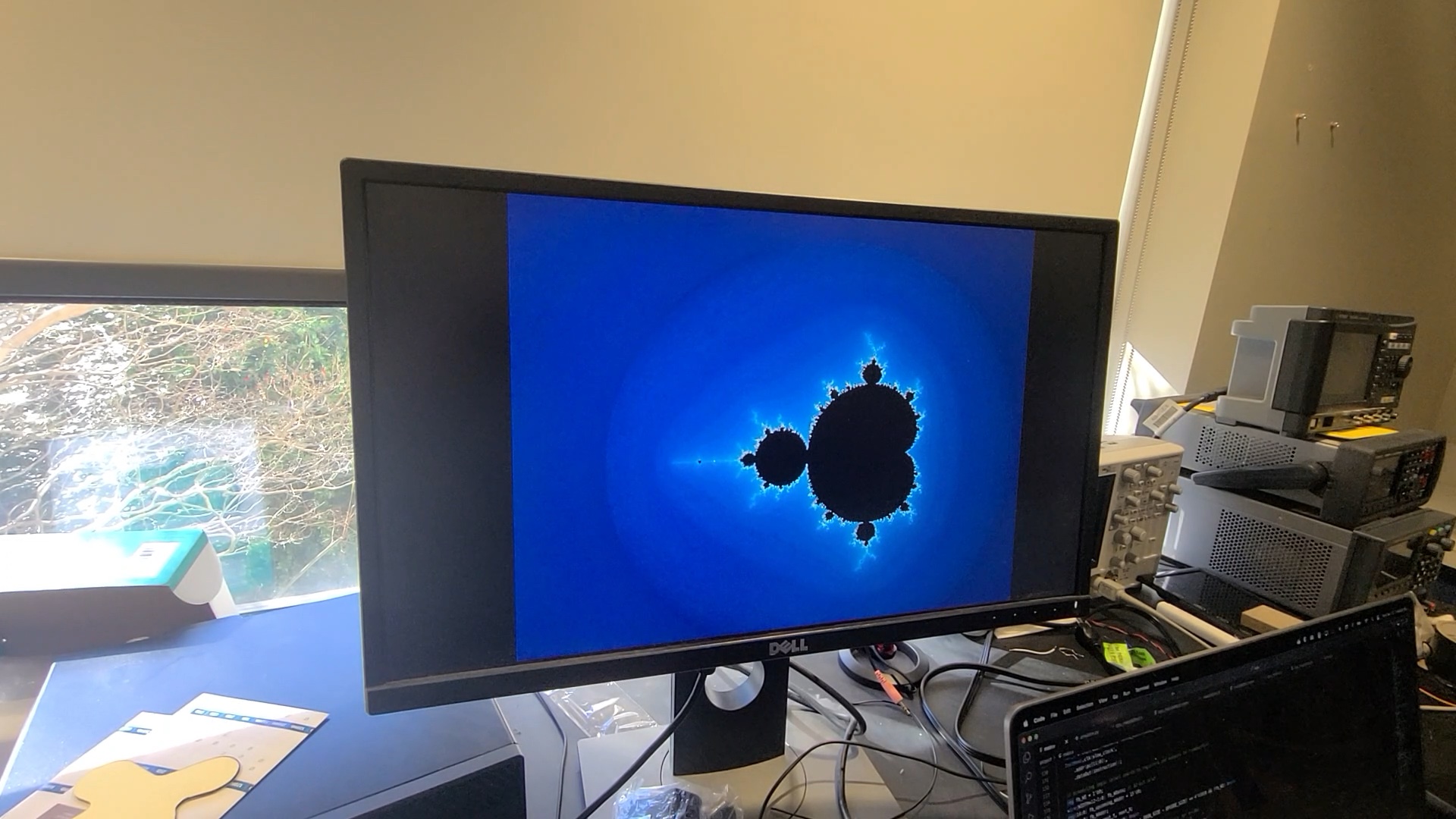

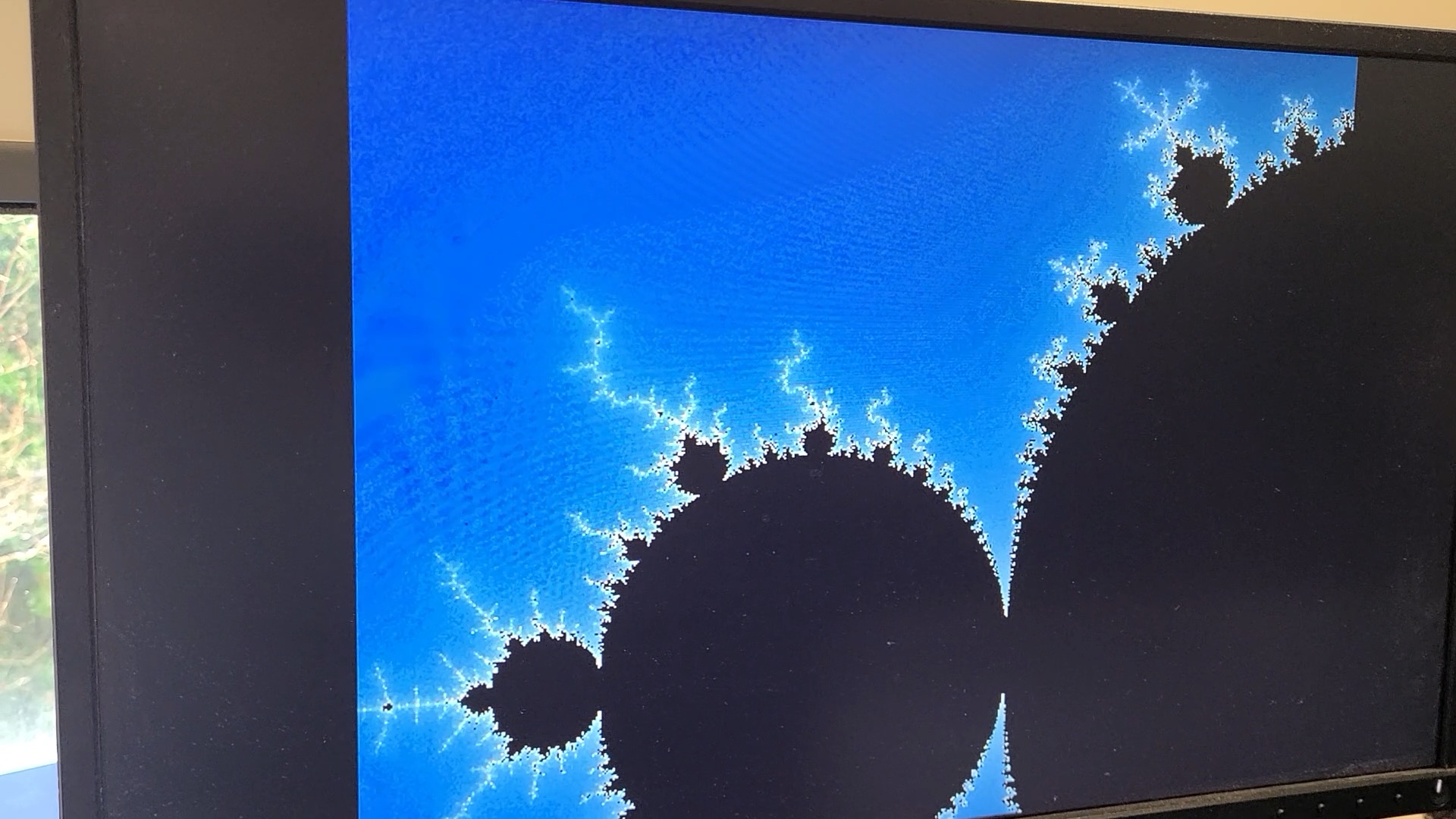

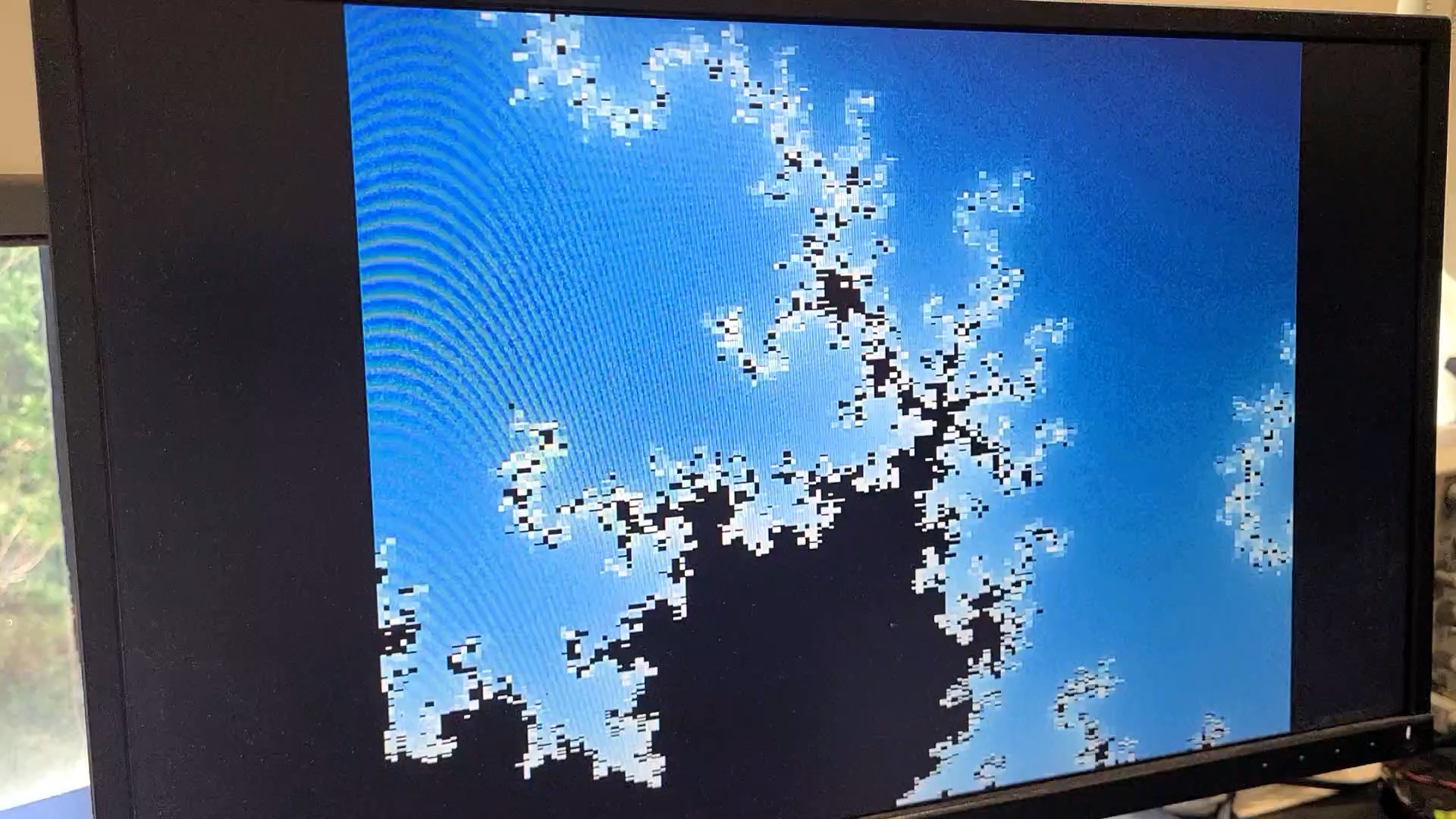

All operations use 16-bit (half-precision) floats, which becomes all too apparent after zooming in only a few times on my Mandelbrot visualizer.